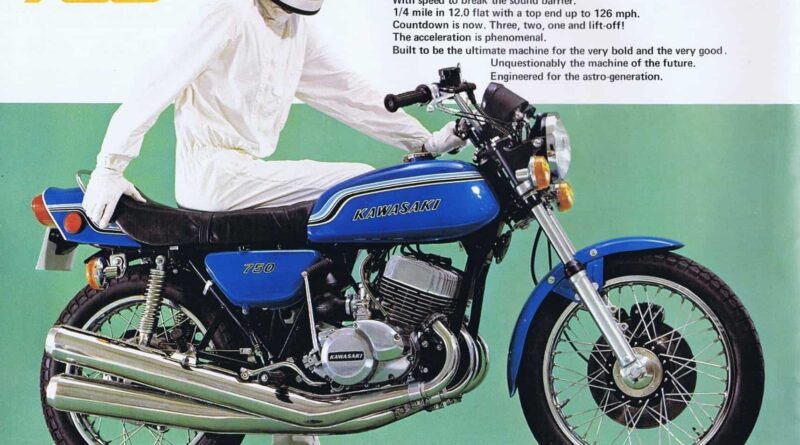

Kawasaki 750 Mach IV H2: The Legend of the “Widowmaker” Lives On!

The “Widowmaker” was noisy, terrifying, and if the rider was brave enough, capable of leaving everything choking on a cloud of two-stroke fumes. So if the 1972 Kawasaki 750 Mach IV H2 was such a bad boy, what made it so revered? Read on to find out more.

When Honda launched the CB750 K1 in 1969, it took motorcycling into a new era. The model had so many advances in motorcycle design and technology, it stunned the biking world.

There was only one problem. And it’s a criticism that has followed Honda through the decades. While the K1 was great at what it did, it was boring. It may have changed the motorcycle world, but it also sanitized it to some degree.

If the 750 Honda was Captain Sensible, then the Kawasaki H2 750 was an out-and-out hooligan. It dragged motorcycling kicking and screaming back to the Stone Age, and bikers loved it.

Why the world was so shocked by the H2 is surprising as it came hot on the heels of its predecessor, the raving mad Mach III H1 500. Although at the time (1968), Kawasaki was in a state of flux, it had the legendary Z1 in the starting blocks ready to go, but with a capacity of 750cc.

Honda beat Kawasaki to the punch in 1969 with the 750 K1. So Kawasaki decided to hang back and bump up the Z1’s capacity to 900cc. This move turned out to be a clever one.

This cautious approach left Kawasaki without a horse in the race, so they decided to move forward with their N100 plan. The top-secret project was to build the fastest street bike on the market.

How did Kawasaki nail the brief?

After much experimentation with various engine layouts, they produced the Kawasaki H1 500 Mach III, which nailed the brief.

The 500cc two-stroke, inline-triple engine was brand new, and to make the most of the air cooling, cylinders were canted forward by 15 degrees. The first motorcycle to feature electronic ignition, the Mach III’s power to weight ratio was close to that of a race bike, and therein lay the problem.

Like Yamaha, Kawasaki was most likely 20 years away from making great frames. Yet, whereas Yamaha went to great lengths to improve the XS 650 frame, Kawasaki didn’t care less. Outright acceleration was the name of the game. If you couldn’t hang on, buy a Honda!

The Mach III’s speed was legendary. Yet, it was its delivery that was addictive and scary. For me, the first time you feel the power band on a big two-stroke engine, the experience stays with you forever.

What makes the 500cc Mach III such a legendary ride?

Just as you’re wondering what all the fuss is about, the bike wheezes its way up the rev counter, and without warning, the engine hits its sweet spot. And this is when all hell breaks loose.

The Mach III’s kick in the pants came in around 6000-rpm, and 3000-rpm later, it’s all over. It’s enough to hoist the front end significantly off the floor on pure acceleration in the first three gears.

Skilled riders could change gear fast enough to keep the bike in the mad zone right through the gearbox. The prize for doing so was to leave behind every other motorcycle on the street regardless of cubic capacity.

The Mach III’s boast of being “the fastest accelerating bike on the road” got backed up at every stoplight drag strip.

The motorcycle became a legend on both sides of the Atlantic. Yet if riders thought the Mach III was a handful, the 750 H2 had speed freaks fainting at the mere sight of its spec sheet.

Launched in 1972, the Kawasaki 750 H2 Mach IV had a 50-percent larger engine and an extra 14-hp taking its power output up to a mind-numbing 74-bhp. To put these figures into perspective, its closest competition, the Honda 750 K1, weighed 50-lb more and could muster only 67-bhp.

The Suzuki GT750 Water Buffalo launched in 1971 fared even worse with 66-bhp and a whopping 530-lb.

What were the H2’s flaws when it came to performance?

The H2 was head and shoulders above every other motorcycle in the power to weight category. But, like its smaller sibling, there was a price to pay, and that was its appalling road manners.

The double-cradle frame was too light, and the swinging arm too short. In addition, the preload-only rear shocks were hopeless, and the non-adjustable front forks were overworked even on a decent road.

With what amounted to a race engine in a pushbike frame, the handling dilemma was made worse still by the bike being back heavy. The H2 needed no excuse to point its front wheel skyward. However, with this adverse weight distribution, the average front tire would hardly see tarmac.

Terrible handling, instant wheelies, serious amounts of power, and underwhelming brakes became a terrifying combination in the wrong hands.

Thanks to inexperienced riders, the H2 had a bad rep, and its name tag, the “Widowmaker,” has stuck.

During its extensive development stage, the 500 H1 had done most of the heavy lifting in terms of R&D. Even though Kawasaki’s sole purpose of the build was to trash the competition, they realized that the extra horsepower of the 750cc needed to come in a more civilized package.

With this in mind, instead of boring and stroking the engine to get the magic numbers, Kawasaki went the long way around building virtually a new engine.

The three Mikuni carbs increased to 32-mm, while the porting was slightly less aggressive. In addition, the compression ratio increased to 7:1. But the big news was the constant discharge ignition. The CDI ignition first featured in the 500cc H1, but running problems saw Kawasaki dump it in favor of points.

By the time of its re-introduction on the 750 H2, the precision and strength of the spark igniting vast amounts of fuel in the combustion chamber were quite literally explosive.

How did the new engine tweaks transform the 750 H2?

With the engine’s new tweaks, Kawasaki managed to pull off quite a trick by transforming the 750 H2 into a real Jekyll and Hyde.

Riding the 500 H1 was like sitting on an unexploded bomb. Below the power band, the engine was so limp it felt like one of the cylinders wasn’t running. But, on the flip side, the 750 H2 had perfect road manners for the first 6000-rpm.

Acceleration is brisk but predictable even if the engine still has that trademark two-stroke handlebar buzz. Most importantly, it is possible to ride around town without fear of suddenly hurtling forward without warning.

Kawasaki even addressed other bugbears by replacing the 500’s largely ornamental front drum brake with a disk. They also supplied the bike with extra lugs cast into the right fork leg to make the addition of a second brake disc easy.

As for the H1’s legendary poor handling, Kawasaki placed a rotary damper on the steering head and an extra frame lug to mount a second hydraulic steering damper. By doing so, the 500 H1’s fatal tank slappers got downgraded to life-threatening weaves on the 750 H2.

Did Kawasaki cancel the party altogether in making the 750 H2 more rideable in the lower rev range? No way, what they did was offer a bike that played well with the other traffic right up until the touch paper got lit. At which time, it was Mr. Jekyll’s turn to come and play.

Thanks to the all-new electronic ignition, excellent fuelling, and clever combustion chamber design, you know when the big Kwak is going to kick off. Wheelies are as much a part of the H2’s makeup as dodgy wiring on a vintage Ducati.

Compared to the opposition, the handling was still appalling, and all the steering dampers in Tokyo don’t make the H2 behave. Instead, it’s the bike’s predictable insanity that makes the Kawasaki 750 Mach IV H2 so appealing.

Is the Kawasaki 750 Mk IV H2 a viable ride today?

Of all the classic bikes we’ve reviewed so far, this question regarding the H2 is one of the hardest to answer. Why? Because the engine being so skillfully put together on an almost bulletproof bottom end, means it’s possible to ride the big Kwak around regularly.

Below 6000-rpm, it will more than keep up with today’s traffic. Slowing down, though, as quickly may not be so easy. Yet, head for the twisties and the average modern 250cc will run rings around it and then some.

You don’t buy one of the early seventies most outrageous hooligan tools to commute on, though, right? No, instead, you buy a “Widowmaker,” find a nice quiet, long straight road and nail the throttle.

Let’s also not forget why the H2 got put out to pasture just three years after its launch, namely noise and pollution. Being used as it should, the 750cc two-stroke engine is a chain smoker, and with around 22-mpg, it’s got a drink problem too!

You may get knowing glances from other bikers of a certain age, but you sure won’t be invited to the next global climate talks.

When talking about the H2’s everyday usefulness, the final thing to consider is related to its two-stroke engine. Roll the throttle off on an H2 at the entrance to a bend, and nothing happens.

Like all two-strokes, there is almost no engine braking to slow you down. Whereas even with a smaller capacity four-stroke bike, time it right, and the engine braking slows you down enough to line it up for the curve.

Why is the engine so challenging to get used to?

The lack of engine braking may not seem like a big deal, but it takes a lot of getting used to, and here’s why. First, line the H2 up for a double bend, and without engine braking, you arrive at the first curve too hot.

For an inexperienced rider, the natural reaction is to grab a handful of brake and kick it down a gear or two. But that’s the beginning of the end. Heavy braking will cause the H2’s under-damped front forks to dive and the back end to wiggle. While you try to stay on board, you either stray into the opposite lane or throw it further over, scraping metal from the poor ground clearance.

While this is going on, you may not realize that by kicking it down a couple of gears, you’ve increased the engine revs to the edge of the power band. So if you do make it to the exit, giving the Kwak, a handful will see it wheelie while still at an angle. If you don’t, the back tire will break free, and over you go.

Either way, you’re chewing tarmac, and this scenario, together with riders panicking when the front wheel came up, is what happened time and time again. And this is why Kawasaki said at its launch; only skilled riders need apply. It wasn’t just reverse psychology marketing, either!

In the right hands, the Kawasaki H2 750 Mach IV is a roller coaster ride that will leave you grinning from ear to ear. It epitomizes a time when motorcycle manufacturers built bikes specifically to trash the opposition at all costs.

What is the true two-stroke experience?

You either love or hate the whole two-stroke experience. I’ve never been a fan. But then again, I had my first Kawasaki triple experience after many years of big-bore four-stroke ownership, and the two don’t mix back to back.

I will never forget riding around on a Kawasaki 500 Mach III with a stage one tune, expansion chambers, and two steering dampers. But, similar to the Pope kissing the ground after a plane ride, I was always relieved to kick it into neutral, which strangely enough was below first gear.

If you remember riding an H1 or H2 in the late 70s through 80s and have kept riding ever since then, my advice is to buy one. If, on the other hand, you remember the experience through a haze of two-stroke fumed nostalgia and think it’s a fix for a mid-life crisis, leave well alone.

Kawasaki said it best back in 1972; “Only skillful riders need apply.”

Even though the H2 is an acquired taste, adding this piece of noisy nostalgia to your collection will not come cheap. A quick look through the classifieds sees an original condition, low mileage version going for between 20,000-22,000EUR. If you don’t mind some modifications like double front discs and a loud exhaust system, the price drops to 12,000-15,000EUR. You can snap- up a rough-looking but complete barn-find for around 8,000-10,000EUR.

See below for table:

Model

ID

SIZE CC

YEAR

FEATURES

Mach III

H1

500

1968

Drum brake front and rear, CDI ignition, electronic ignition sticker on oil tank, fastest bike on the street

Mach III

H1A

500

1971

Change to brighter paint jobs

Mach III

H1B

500

1972

Steering damper, new paint job, CDI dumped for points ignition. Front disc brake. Model runs until 1976

Mach IV

H2

750

1972

Front disc brake, rotary steering damper, CDI. Takes the fastest bike on the street crown

Mach IV

H2A

750

1973

Seat and tail section wider

Mach IV

H2B

750

1974

All models redesigned to look more like the Z1, instrument pod, 3hp power reduction, fork rake increase

Mach IV

H2C

750

1975

The famous 2-tone purple paint job marks the end of the run for the meanest production bike ever built

The post Kawasaki 750 Mach IV H2: The Legend of the “Widowmaker” Lives On! appeared first on Old News Club.