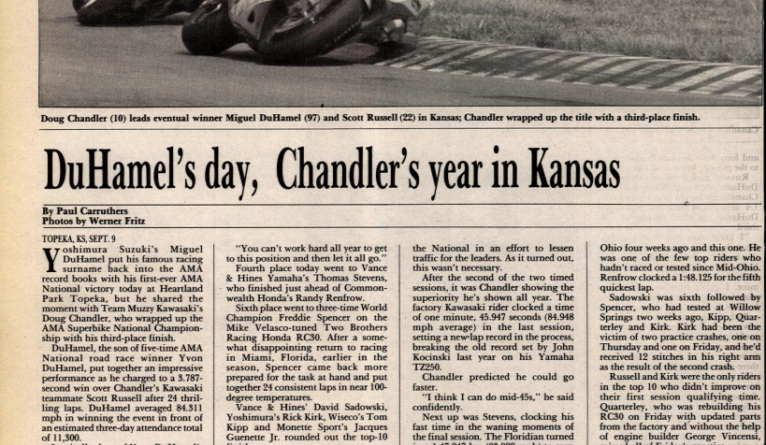

21 In ’21: Doug Chandler, The Last Of The Dirt Trackers

The following is the eighth in our 21 in ’21 features that highlight one of the 21 AMA Superbike Champions each week as we move through the 2021 MotoAmerica season – the 45th year of the premier class championship.

Much like the Bubba Shobert, who preceded him two years earlier in the list of AMA Superbike Champions, Doug Chandler was first and foremost a dirt tracker. Though he never won an AMA Grand National Championship, he was usually in the thick of the battle for a title he dreamed about as a kid. And, as the last of the breed of dirt trackers turned road racers, Chandler is also the fourth and last rider to win the coveted Grand Slam – victories in all forms of dirt track (mile, half mile, short track and TT) as well as a road race national.

Eventually, Chandler started to compete in road racing in order to pad his standings in the AMA Grand National Championship, which at the time included all forms of dirt track as well as road racing. Turns out he was quite good at it, and it ultimately led to not only three AMA Superbike titles, but a shot at 500cc Grand Prix racing.

“I started racing in 1972,” Chandler recalls. “I got my first trophy with the intent of flat track only. I didn’t see anything else. It wasn’t until later on when I first started doing the professional flat track racing that I kind of got a little bit of an idea what the road racing was like. I think Honda gave us a great opportunity. At the time it was Ricky (Graham), Bubba (Shobert) and myself racing for them on a flat track championship thing. They thought it would be a good idea to put us on road race bikes when the racing didn’t conflict. At the time, we had RJ Reynolds sponsoring the series and it was a combined championship. I think Mike Baldwin probably could have top-10’d it if they had more road races during the year, but at the time I think they only had maybe seven, eight, nine, versus we were doing 30 flat tracks a year. So, the number of events kind of canceled out those guys on the road racing, but it entitled us or gave us the opportunity to possibly gain more points. They saw that, and that’s what kind of got us into the road racing.

“It wasn’t until then that I had seen the bigger picture of how much more there is to this motorcycle business. Like I said, going into it, flat track was all I had my sights on, but going to the road races and seeing all these other manufacturers involved rather than just a Honda and a Harley – you had the Kawasaki, the Suzuki, and all these other manufacturers. It was another step. I was pretty much at the end, as far as I could take the flat track thing, to where road racing was growing in America as well as if you had the opportunity or chance, you could go over and race in Europe, Japan. There were a lot of other places you could go do these things at. So, that’s what kind of got me turning the other way on all of it.”

Chandler continued to race dirt track right up until the season when he earned his first AMA Superbike title.

Doug Chandler at speed in 1990 on his Muzzy Kawasaki.

“In ‘89 and ’90 I signed a two-year deal with Kawasaki,” Chandler said. “’89 was my last year they allowed me to flat track. It was kind of a bummer. It was nice to kind of be able to still do the two, but I kind of understood their side of things. They started getting a bit of money behind you, invested in you. You need to be careful what you do, and they want you to be able to make all the races, and if you were to get yourself hurt doing something else other than racing for them, it could be a problem. So that was when I kind of had to hang up my steel shoe, so to say.”

By the time Chandler was fully vested in road racing, the AMA Superbikes had evolved into good racebikes – a far cry from the early Superbikes ridden to titles by men like Wes Cooley and Wayne Rainey. Still, they were a far cry from what John Doe can purchase at this local dealer in 2021.

“We still had carburetors on those bikes,” Chandler recalls. “I think it all was similar, but it also has I think evolved a lot faster than what I would have thought it would have. The stuff nowadays, even on a brand-new streetbike off the showroom floor, the electronics on it are unbelievable. That was something we didn’t really… It was coming into play my last couple of years over in Europe, and then coming back to America and racing the Superbikes. It was kind of moving forward leaps and bounds to where, like I said, the early stuff, carburetors, bare minimum of anything. The only thing electronic on the bike was the ignition and the tach. Everything else was mechanical, manual.”

Chandler got his real taste of what trick stuff really was when he raced the Cagiva in 500cc Grands Prix in 1993 and 1994.

“I think a big thing in ’90 on our bike was we had an electronic exhaust valve. That was the thing back then. Like I said, you think about that, that was 1990. Where everything is now, it’s huge. Like I said, over in Europe on the 500s we had some pretty cool stuff, but it was electronically driven. We had sort of an electronic shock, but it was essentially a three-position map switch that would control essentially being able to adjust the rebound and the compression knob for different corners on the track. We had a map on a bike and a three-position switch. Again, that was pretty cutting-edge stuff back then. And it worked pretty good. I would sort of say our biggest problem on the Cagivas, we were using a Showa shock, it was an aluminum body with the two pipes going around that thing out the back. It would get really hot. During the race distance, it would kind of fade and kind of set down. So, we really used that map switch. Being able to change the shock mid-race to where it would still kind of hold up or keep the ride height the same. That was a big thing for us back then. I think the speed shifting, that started coming about early ‘90s as well. That was again something that was huge. You think about now, the transmissions in these modern GP bikes are just unbelievable. It’s pretty cool.”

In 1991, Chandler got the option of racing in the GPs on a Yamaha fielded by three-time 500cc World Champion Kenny Roberts or stay with Kawasaki and go World Superbike racing. He chose door number one.

“I had a choice,” Chandler explained. “I was given a pretty good choice. Kawasaki wanted me to stay, and they were going to start a World Superbike team. They wanted me to do that, but then I had Kenny (Roberts), on the other hand, offering me or giving me the opportunity to go race a 500. The pay was the same and even if the pay was a little bit lighter on the 500 side, to me, I think any rider or racer, your ultimate goal if you’re a true racer is to race in the top level, premier class and just see how you stack up. So, to me, it was a no-brainer. I kind of had the opportunity. It was like, I want to go do this. I enjoyed it. It was a lot of fun. Who’s to say what we would have done on a Superbike? I think anybody, even today I think that’s kind of the going thing if you have the chance to go do the GPs, that’s going to be the preferred class versus the Superbike.”

Back then, not all the bikes in what is now MotoGP were created equal. As Chandler found out. In 1991, Chandler finished ninth in the 500cc World Championship in his rookie season with Roberts; in 1992, he was a factory Suzuki rider in 500cc GP, and he finished fifth in the World Championship; in 1993 and 1994, he was a factory rider for Giacomo Agostini’s Cagiva team and he ended up ninth and 10th in those two seasons, the highlight of which was his second-place finish in the Argentinian Grand Prix in 1994.

“I think all the bikes in the MotoGP class right now, all 21 or 22 of them, I think they’re all capable of winning a race to where we might have had a few more guys on the 500 back in the day, but the guys in the back… It would have taken a lot for them to win a race,” Chandler said. “The thing I see now, back then again without the electronics, you kind of had to ride the thing with what you would say throttle control. I think my background in the flat track helped me kind of deal with a more powerful bike. You couldn’t just mad the thing out of the corner. You had to kind of pedal it, squeeze the throttle, and just roll into it, especially when the tires would go off. Now, again with all the electronics, that kind of takes that out of play, which I’m kind of bummed. I like how everything is going forward electronically, but I would really, really like to see who could ride one of those things without any of the assists on it, where you had the full power into your hand. You had full control and not just relying upon the computer guy on how it comes into play.”

When Chandler couldn’t find a Grand Prix ride in 1995, he came back to the U.S. and AMA Superbikes. But not with Kawasaki. And not with a lot of anything to show for it but pain.

“’95 was a short year,” he said. “Couldn’t find nothing to keep me in Europe. Came back over here. All the seats were taken here. I rode the Harley-Davidson (VR1000). First race of the year at Daytona, I don’t even make it a lap. I get punted in the last corner of the infield, break my collarbone. Come home, get that plated and put back together. I think within a month, month and a half we were testing at Laguna Seca. (I) Lose the front up into the Corkscrew. Fall on the same shoulder, break the plate, mess up my shoulder. So, I was out pretty much half the year. It was kind of a bummer. I enjoyed working with those guys. Again, over in Europe, I kind of got more involved in when we were getting more of the electronics stuff, not so much in assistance on the bike but I think the telemetry, being able to look at the suspension. That was a big thing back then when I was over there, actually seeing chatter on a graph on the computer from your front forks, seeing the ride height of the front and the rear. I kind of jumped into that with both feet. To me, it was a good tool to understand what the bike was doing underneath you. It was good to be able to describe it to the mechanics what the thing is doing, but to be able to see it on the computer and point it out to them, I think that made a big improvement as far as developing the bike, getting things sorted out quicker and being able to go around the track faster.

“So that when I came back to America, it was new to these guys over here. So that’s kind of what I really focused on. I’ve always enjoyed that side of the thing as well. I never put myself in a position to where I felt I was always the best rider. To me, I know there were other guys out there way more talented than me. Anthony Gobert was a good example. To me, my edge on them was I was going to have a bike that was going to work better, save the tire, have something at the end of the race versus just wearing out, smoking off everything and having nothing left. That’s how I kind of looked at all the racing side for me.”

Chandler won two more titles in 1996 and 1997 – the heyday of AMA Superbike racing in many respects.

Chandler, with son Jett on his lap, chats it up with his rival Miguel Duhamel.

“It was a good time. I feel very fortunate to be a part of that. I think in the day, I think the first 16 guys were all factory riders. That’s a pretty deep field. When I came back – again like I said I kind of described my first year back in ’95 with the Harley guys. That was kind of a bit of a bummer for me. The way I came back from Europe, I wasn’t ready to come back. I just had no place to go. So, I was a little bit bummed about that. Then all the stuff we went through in ’95, I was pretty much over it. It seemed like no matter what we did, I had things going against me. There was a time where I was just like over it. I think anybody, if you do anything for any length of time, I guess it’s pretty easy to get burnt out or just kind of want to throw your arms up. But every time I’d start thinking that, you’d sit back and realize all the years you’ve been doing this, all the friends you’ve made. What else would there be for you to do? It would be like starting over to where you stay involved with the racing. You know people. There are good times as well as bad times. It’s just getting through the bad times. So, I kind of took it on again. I had Gary Medley with me there at Muzzy, and Rob (Muzzy). He’s been a good guy since day one. I kind of go back to ’84 with Honda. I had my father-in-law, Jerry Griffith, doing all of my stuff and Honda brought Rob in, who was doing Ricky’s (Graham) stuff. So, I kind of had a bit of a relationship with him then. Then he got in and did the Kawasaki road race team. So, it was nice. It was nice to be back on a proven team, proven bike. You kind of eliminate any doubts or questions and just get on the thing and have fun, pretty much. I was able to do that, and we won two more championships.”

Fast forward to 1998 and a bit more adversity for Chandler.

“1998 was a tough year,” Chandler said. “That went all the way to Las Vegas, the final race for the championship. It ultimately was with me and Ben (Bostrom). That was a really tough weekend. We were in the running for the 600 (Supersport) Championship as well as the Superbike, and to come out of there with neither one of them… That year was tough. I think that was the year I took out (Akira) Yanagawa the top of the Corkscrew (in the World Superbike race at Laguna Seca). I didn’t break nothing, but it gouged the inside of my right knee pretty good, so it kind of was uncomfortable and kind of odd to ride a road race bike with high pegs, knee bent. It was kind of restrictive. I didn’t have a full range with my knee. I think that was one of the craziest years because we had so many guys capable of winning the championship. Anthony Gobert was in good form. (Mat) Mladin was going well. It just seemed like anytime anybody would kind of get up front and would be leading the championship something would happen, they would break or wreck or do something. It was almost like nobody wanted to win the championship that year. Ultimately, it ended up going down to the final race with me and Ben, and we sprung an oil leak. I was oiling my tire and went backwards. So, it kind of hit me as well, but it was all good. I think ’99 was the last year with the Muzzy team, and then it all kind of went in-house. That wasn’t not a tough time for me, but they were going a little bit of a different direction than what I would have liked to have seen it go. So, I kind of struggled and from then on. I think it just kind of went downhill for me.”

The next phase of Chandler’s career saw him still involved in motorcycling – with MotoAmerica.

“I still rode for a fair bit. I kind of messed around with doing my own little schools, and that was fun. I still do enjoy riding a motorcycle. Maybe not so much on the road stuff, but I am definitely back on flat track bikes and dirt bikes constantly throughout the year. So, I still ride a fair bit. When MotoAmerica started, I kind of wanted to do my part or do what I could to be involved with that, so I started with them as a rider representative. It was kind of a different position. Growing up, or all the years prior, being in the paddock, being on the racing side of things to where now I’m essentially on the other side of the fence and I’m an official, it’s a little bit different of a look. You still have your friends, but definitely you see how they looked at you was a little bit different than previously when you were another competitor. But I enjoyed it. It was a lot of fun being on that side and doing what you could. I think the first two years I did that, and then they kind of worked me into being a race director. I did that for a few years as well. Enjoyed it. It just was a bit stressful at times, having all the pressure on you, making the decisions. But I had a good team in Race Control with me. We kind of all covered each other and watched our backs, so I thought we did a really, really good job.”

And now? Chandler owns a bicycle shop in his hometown of Salinas, but he still aspires to be a team owner in the MotoAmerica Series.

“To where I am now, ultimately trying to get back to the racetrack, preferably back on the other side of the fence in the paddock with a team of my own. That would be my ultimate goal. If I could do that, I would be really happy.”